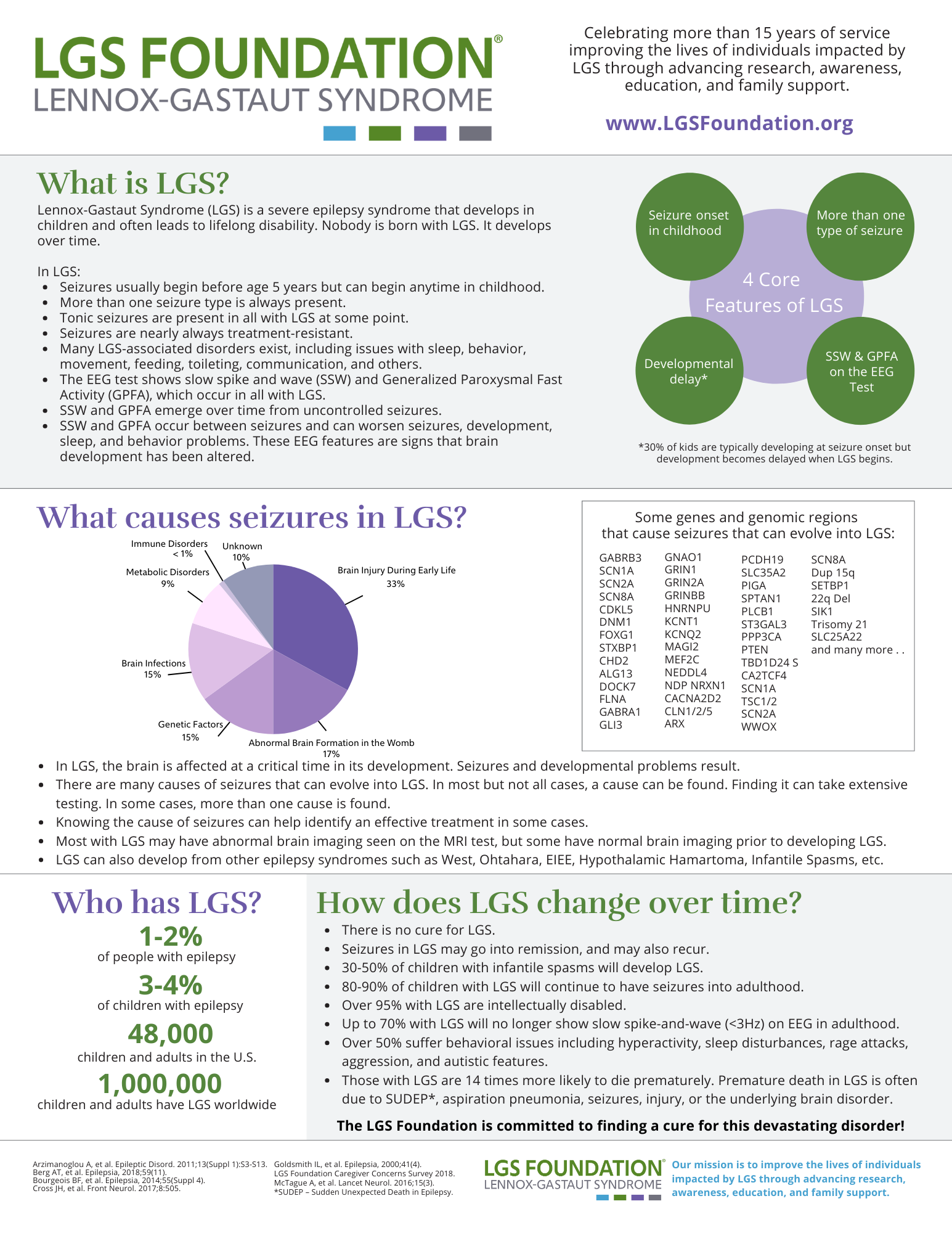

What is Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome?

LGS is tough. So are we! As you read about LGS, please remember that you are not alone.

Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome (LGS) is a severe epilepsy syndrome that develops in young children and often leads to lifelong disability.

Nobody is born with LGS. It develops over time. LGS is a rare disease (approximately one person in every 2,000).

About 50,000 people in the United States and 1 million people worldwide have LGS.

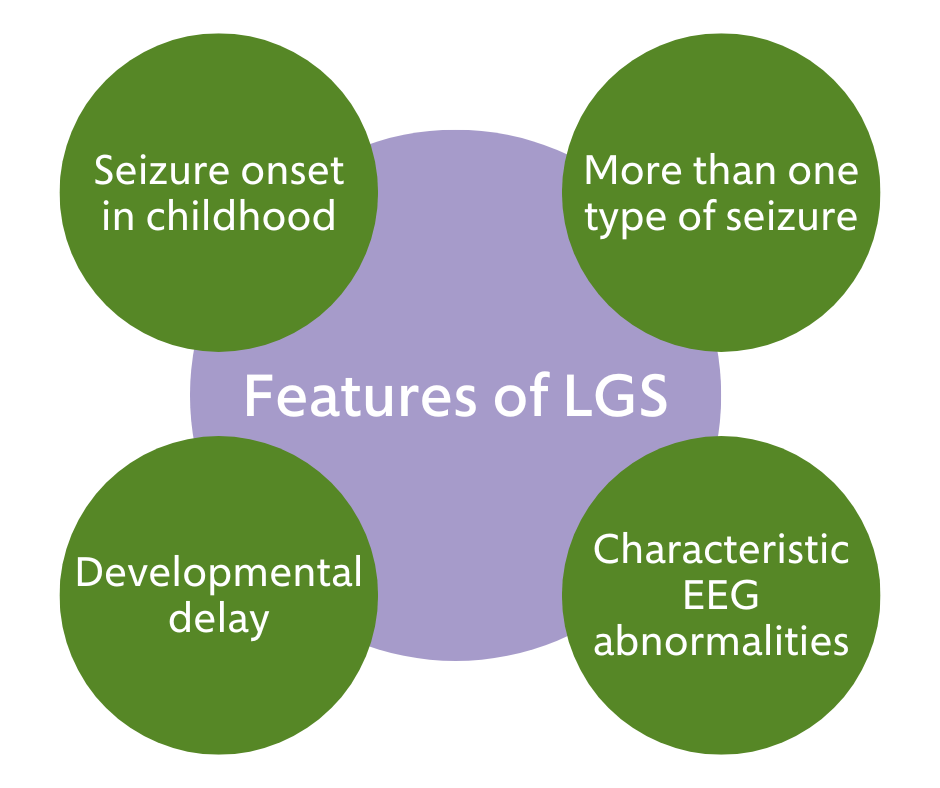

The 4 Core features of LGS

There are four key features of a diagnosis of LGS:

Seizures begin in early childhood.

-

- Most with LGS have seizures that begin in the first three years of life. However, seizure onset in LGS can occur at any time in childhood.

More than one seizure type (tonic seizures occur in nearly all with LGS). Seizures regularly continue despite treatment.

-

- Check out our Seizure Types Associated with LGS Page

Abnormal brain waves on the electroencephalogram (EEG) test. These include:

-

- Slow spike-and-wave (SSW)

- Generalized paroxysmal fast activity (GPFA)

Developmental delay and/or intellectual disability.

-

- Not all who are diagnosed with LGS have a developmental delay at the time of diagnosis. However, nearly all with LGS will have developmental delay within five years of seizure onset.

LGS 101 for Newly Diagnosed Families

Other things to know about LGS

- Slow spike and wave (SSW) and Generalized Paroxysmal Fast Activity (GPFA) are seen on the EEG. These are the hallmarks of LGS. Diagnosis of LGS requires an EEG test.

- SSW and GPFA usually emerge between ages 3-5 years but can begin later in childhood.

- SSW and GPFA, which occur between seizures, worsen seizures, development, and behavior problems.

- Seizures that evolve into LGS can be due to a wide range of causes.

- While we know much about what causes early-life seizures, we do not know how seizures evolve into LGS.

- LGS may develop in children without a history of epilepsy, although this is rare. The majority of the time, LGS evolves from another type of epilepsy.

- Severity differs to some degree between patients. However, LGS is considered very severe.

- Many with LGS survive into late adulthood, and most require lifelong care.

- Those with LGS have an increased risk of:

-

- Falls and injuries from seizures

- Aspiration pneumonia (inhaling saliva during a seizure resulting in pneumonia)

- Early death, including Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP)

-

- LGS is a rare disease and one of the Developmental and Epileptic Encephalopathies (DEEs).

More About the Signs and Symptoms of LGS

Many LGS Associated Disorders exist, including issues with sleep, behavior, movement, feeding, toileting, communication, and many others.

- Tonic seizure. This is the most common type in LGS. They consist of neck, and sometimes arm and leg, stiffening. They often involve eye-opening and upward eye-rolling. They often occur in sleep. They can be subtle and easily missed. An overnight-video laboratory test can reliably detect them. If they occur during the day, while a child is upright, they can result in a fall.

- Atypical absence seizure. This type consists of brief blank-outs where a child is less aware.

- Atonic seizure. In an atonic seizure, a child abruptly loses body tone and slumps. If these occur while sitting, they can look like a quick head nod. If they occur while upright, they can lead to abrupt falls and injury.

- Myoclonic seizure. These consist of isolated, brief body jerks.

- Focal impaired awareness seizure. These typically begin with staring and altered awareness. This lasts up to several minutes and is followed by a period of confusion. These seizures can progress into generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

- Tonic-clonic seizure. These consist of generalized stiffening and rhythmic shaking. Seizures often change in children with LGS as they grow and develop.

- Aggression

- Autism spectrum disorder

- Inattention

- Hyperactivity

- Problems with balance and coordination. This is a common motor difficulty.

- Problems with feeding and swallowing. A small number require a feeding tube.

- Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP). This is a major concern in LGS. The exact cause of SUDEP is not well understood. However, it may be related to post-seizure heart and breathing issues. Those with frequent convulsive seizures are at the highest risk.

- Infection. Lower mobility can lead to infection. Pneumonia is an example.

- Accidental injury. Seizures, particularly atonic or tonic seizures, may cause falling and injury.

Is there a cure for LGS?

- There is no cure for LGS.

- Seizures may go into remission but may also recur.

- It is important to try to achieve the best possible seizure control in LGS.

- Seizure management options include anti-seizure medications, specialized diets, brain surgery (e.g., corpus callosotomy, deep brain stimulation), and neurostimulation.

- There are currently no therapies that target the EEG features of LGS (e.g., a disease-modifying therapy).

What is likely to happen in the future for those with LGS?

- The prognosis for LGS is poor, and the progression of LGS is almost always associated with developmental slowing and/or regression.

- Despite the best treatments, more than 85% of children with LGS will continue to have seizures into adulthood. The LGS Foundation is working hard to change this.

- Because of the abnormal brain waves in those with LGS, more than 90% have significant intellectual disabilities. The LGS Foundation is also working hard to change this. It is believed that seizure control is key to improving developmental outcomes in LGS.

- A few with LGS live a generally normal life, but more than 50% with LGS suffer many LGS Associated Disorders (LAD), including communication issues, balance issues, behavioral issues, sleep disturbances, rage attacks, aggression, autistic features, and other issues.

- Those with LGS can live into their 50s or 60s but are also more likely to die prematurely due to the underlying brain disorder, seizures, injuries, accidents, aspiration pneumonia, or Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP).

LGS Fact Sheet

- Get the Facts – Download the LGS Fact Sheet

- Download the LGS Fact Sheet in Spanish

- Review the LGS Natural History Study

Thank you to the Child Neurology Foundation for allowing us to adapt this article for this site. Authors: Shaun Ajinkya, MD; Elaine Wirrell, MD, Mayo Clinic – Rochester, Minnesota

The information here is not intended to provide diagnosis, treatment, or medical advice and should not be considered a substitute for advice from a healthcare professional. The content provided is for informational purposes only. LGS Foundation is not responsible for actions taken based on the information included on this webpage. Please consult with a physician or other healthcare professional regarding any medical or health related diagnosis or treatment options.

Updated 10/25/24 (KK)